Don’t be the link.

Are We Connecting The Links?

President/CEO at The Aviation Consulting Group, Inc.

Published Dec 17, 2022

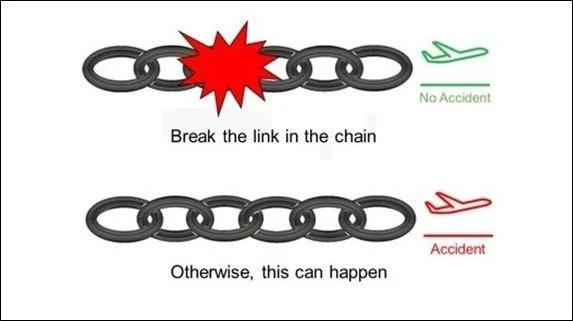

You have heard of “the error chain.” When an accident occurs, it is the result of all the links in the chain connecting. Each “link” can be thought of as a contributing factor in the accident. Some error chains can be quite long, while others may only have a few links. In either case, the links typically (but not always) follow a sequential order. Thus, if we are able to break one of the links in the chain, we can prevent an accident from happening.

After an accident occurs, the investigation reveals all of the links in the chain. The links become clearly visible, albeit in hindsight. Fixes can then be made, but this is a classic example of a reactive safety process. A better option would be to break links in the chain before the accident ever happens. Having no links at all would be even better!

Breaking the links in the chain before the accident happens is a proactive—versus reactive—approach to safety management. But is it even possible to know if you and your co-workers are connecting the links in the chain right at this moment? The answer is YES. In fact, every single day, error chains are broken that may have led to an accident. We just don’t hear much about broken error chains because, quite frankly, there isn’t a whole lot to talk about. Conversely, when the links do connect, and an accident does happen, there is, unfortunately, a lot to talk about!

Here are just a few examples of how error chains get broken (on a daily basis) at an aircraft maintenance facility. Because an aircraft maintenance technician (AMT)…

Verified a procedure

Did not skip a step on a task

Properly completed an operational/functional check

Made no assumptions

Did not sign off work that was not actually completed

Spoke up when asked to do an unsafe task/job

Asked for help when needed

Prevented distractions, such as using a mobile phone, especially when working on a complex task or procedure

Did not use undocumented procedures

Did not “go with the flow” when the flow was unsafe

Many of the maintenance-related aircraft accidents we are all too familiar with had one or more of the above links connect in the error chain (e.g., Air Midwest Flight 5481, British Airways Flight 5390, Continental Express Flight 2574, and Eastern Airlines Flight 855). In each case, if just one of the links in the chain were knocked out, these accidents probably would not have happened.

So, the next time you are tempted to deviate from a procedure, work three 14-hour shifts in a row, or skip a functional check, first ask yourself the following question: Could what I am thinking about doing (or not doing) be part of an error chain? If so, it would be a good idea to reconsider your decision. Your action could be a link in a chain that causes a catastrophic maintenance-related accident with multiple fatalities. Some AMTs learned that the hard way. Don’t let the next AMT be you!